Making Sense of Music Ecosystems — Hints from Environmental Science

James Rhys Edwards, SINUS-Institute Berlin

In recent days, the terms “cultural ecosystem” and “music ecosystem” have broken into the first rank of buzzwords. The European Union’s Music Moves Europe initiative uses them. City cultural officers use them. Music business consultants use them. But what do they mean?

At worst, “ecosystem” can function as a metaphor that sounds sophisticated (and “green”) without adding much analytical clarity. Yes, music scenes are complex. Yes, they involve many interconnected actors. But calling something an ecosystem doesn’t automatically help us understand how those connections work, what makes scenes resilient or fragile, or where interventions might help.

Building on our own work and that of several Music Moves Europe contributors, the OpenMusE project tried a new approach: adapting a proven framework from environmental science to operationalise the interconnections that characterise urban music scenes. The results from live music censuses in four European cities—Helsinki, Lviv, Mannheim, and Vilnius—show the promise of this approach, as well as directions for its refinement.

Thinking outside the (music) box

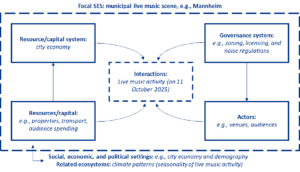

Based on its flexibility, we adapted the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF), developed by Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom to understand how communities manage shared resources. Her key insight was that sustainable resource management requires understanding five core elements and how they interact:

- Actors: Who’s involved?

- Governance systems: What rules and rule-setting institutions shape behaviour?

- Resources: What’s being used?

- Resource systems: What systems enable resource development and circulation?

- Interactions: How do these elements combine to produce outcomes?

The beauty of Ostrom’s framework is that it’s both comprehensive and transferable. Researchers have successfully applied it to everything from coral reef fishery management to public health systems during COVID-19.

Applying the SESF to music required some creative adaptation. Musical practices and cultural value don’t fit neatly into categories originally designed to measure fish reproduction rates or hospital bed availability. So, we extended Ostrom’s “resources” to include not just material goods (venue spaces, instruments, transportation infrastructure) but also what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called different forms of capital: economic, social, cultural, material, and symbolic (etc.).

Suddenly the framework clicked into place. A municipal live music scene is a social-ecological system made up of:

- Actors, including venues, audiences, musicians, promoters, and policymakers

- Governance systems, including zoning regulations, noise ordinances, licensing requirements, and collective rights management

- Resources/capital, including venue spaces, cultural funding, the social capital embodied in music stakeholders’ formal and informal networks, the cultural capital imbued by its formal and informal education systems, and the symbolic capital of a city’s musical reputation

- Resource systems, i.e., the infrastructures through which resources/capital circulate—property markets, grant programs, transportation networks, etc.

- Interactions—in this case, gigs themselves, plus all the activities leading up to and following them

All these elements are furthermore impacted by – and feed back into – broader social, economic, political, and ecological settings. Borrowing again from Ostrom, we can visualise these elements’ interdependencies:

What We Found in Mannheim

We applied our modified social-ecological systems framework to survey and interview data collected in a “live music census” of four European cities, documenting all live music activity during a 24-hour period in October 2024. In Mannheim, Germany—a UNESCO City of Music—we identified 70 venues, surveyed 18 of them in depth, and collected responses from 68 audience members.

Organizing our findings using the SESF gave structure and clarity to a wide range of findings, yielding new insight on:

- Actor vulnerability: Mannheim has a healthy number of small grassroots venues, mostly clustered downtown—while larger venues sit in the city outskirts. But Mannheim’s small spaces face mounting pressures: post-COVID audience uncertainty, economic volatility, noise complaints, uneven access to grants, etc. As one nightclub manager told us, “beverage-based gastronomy… is down by 34 percent in 2023 compared to 2019 in Germany. I’d like to see the manager who remains relaxed about that.”

- Resource gaps: Public transportation exists, but 18% of audiences still cite it as a barrier to attending live music. Cultural funding is available, but navigating bureaucracy remains challenging. As one venue manager put it, “What we would like most from the government would be easier access to more money. Or in simple terms: more money and less bureaucracy.”

- Governance tangles: While Mannheim’s cultural institutions are supportive, dense regulation can create friction. Venues need hospitality licenses if serving alcohol, some need noise impact studies for permits, and some late-night events require special waivers. These aren’t inherently bad policies, but they interact with audience uncertainty and resource constraints (rising rents, tight margins) to create fragility.

- Audience engagement: Despite challenges, audiences value the scene deeply. When asked why live music matters to Mannheim, respondents wrote: “Music is oxygen!” and “Only a city with a healthy MUSIC SCENE can have a healthy population!”

Why This Matters

The SESF approach offers three practical advantages over looser “ecosystem” thinking:

- Structured comparison: Because the framework is consistent, we can compare Mannheim’s music scene with Helsinki’s or Vilnius’s using the same categories. This reveals which challenges are local and which are systemic. We can also compare across scales: the framework is flexible enough to be applied to anything from the entire EU music economy to an individual venue or organisation.

- Systems thinking: Instead of treating the problems facing certain players (like small venues or independent musicians) as isolated, the framework shows how actor vulnerability connects to resource scarcity, which connects to governance constraints, which connects back to audience access. You can’t fix one without understanding the others.

- Intervention mapping: By identifying specific bottlenecks within each sub-system—late-night transport, cultural funding bureaucracy, noise regulations, etc.—the framework empowers music advocates to make concrete policy interventions rather than vague calls to “support the music scene.”

From Analysis to Action

Our research is ongoing, but early findings suggest several policy directions:

- Protect central grassroots spaces through noise-mitigation support and predictable funding, as these venues are most vulnerable yet most valued by audiences

- Improve night-time public transportation to reduce attendance barriers, especially for younger audiences with budget constraints

- Streamline cultural funding access to reduce bureaucratic overhead for small organizations

- Develop “culture district” zoning to provide regulatory protection for music spaces

None of these recommendations are novel. But the SESF framework gives us a systematic way to ground them on concrete data, thus making a much stronger case—especially when pitching toward policymakers who don’t know the sector.

As European cities face economic and technological disruptions, demographic changes, and climate pressures, maintaining vibrant cultural scenes isn’t just about aesthetics—it’s about urban resilience and population health. Music ecosystems connect communities, support creative economies, and make cities liveable. Understanding how these ecosystems work is the first step toward helping them not just survive but thrive.